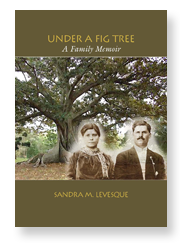

The Last Explanation Cu' ad autru 'nzigna, When grandparents die, the last explanation goes with them. Nearly 40 years have passed since my maternal grandmother, Antonia Maria Delpopolo Scafidi, left us with the indelible spirit of a life that her children and grandchildren love and strive to remember. I am twice removed from her story. Time has diluted the thin details of what she and my grandfather chose to share, and the whole truths were never really accessible. Perhaps it was too painful for them to remember who and what they left behind in Sicily, to say nothing of how they carved out new lives an ocean away. For their children, my mother and her three sisters, first generation Americans trying to assimilate to a culture in conflict with that of their parents, it may have been easier to forget. Or, it may be the "vertiginous" tradition of Sicily, "the secret island", as Giuseppe DiLampedusa described his homeland in the classic historical novel, The Leopard. This is a place "where, in an ostentatious show of mystery, houses are barred and peasants refuse to admit they even know the way to their own village in clear view on a hillock within a few miles walk." Under a Fig Tree started at my grandmother's kitchen table when I was old enough to be curious and young enough to be trusted with secrets, which are hard to have and to hold at any age. The family memoir is my attempt to retell the stories pried from this reticent woman with the added perspective of historical research. Her daughters' first-hand accounts of growing up with Mamma and Papa in the pre- and post-Depression years of their childhoods add the color vision. Interspersed are personal recollections, snapshots of a fading time and place. The photographs and documents my grandparents brought with them peel back more layers, filling in long-standing blanks in the family narrative and providing a few surprises, as well. My first visit to Sicily in August 1997, and the research trip to my grandparents' "hometowns" of Randazzo and Castiglione di Sicilia that followed in October 2007, gave me authentic, first-hand experience to become a believable storyteller. I returned from my last trip with a new twist on our family's old story, quite different from the hand-me-down interpretation of my grandparents' lives. For me, the worn threads of melancholia, loss, and struggle faded when I began to appreciate the rich tapestry of their daring and transforming experience as part of the largest human migration in modern history. I believe that my grandparents did realize the American dream. They also suffered hard realities unimaginable in their youth. But the complete story of their lives, the last explanation, was buried with them and all of the other first generation immigrants, who truly experienced the "old country" in full nuance. The women passed along the secrets of la cucina to their daughters and to their sons' wives. The men formed closed societies that perpetuated the Sicilian sense of localism with secretive meetings of the brotherhood. Together they celebrated the feast days of their Sicilian villages' patron saints with annual festivals, familiar food, and pageantry. They named their children in honor of those left behind, without any explanation or resistance as immigration officers, parish priests, doctors, and teachers Anglicized their first and family names. Regardless, in their new world they fiercely protected their identity as Siciliani first and Italians second. They were the dominant forces in their communities, adhering to the social life, entrenched eating habits, and rituals of their villages. Their children, the transition generation faced with bridging both ways of life, were called Italian-Americans, albeit more Italian than American. They knew little of life in the old country, which made it easier for them to let go of their parents' customs and connections. The Italian-American ratio eventually reversed itself as their descendants melted into the great American society, fully adopting a new way of life. It seems that every Italian girl has a story about Nana.* This is mine. * * * *The correct dialectical spelling of grandmother is Nanna, as is Nannu for grandfather. There is a tendency in many Italian-American families, including ours, to de-emphasize the double consonant, which is why I use the familiar Nana and Nanu throughout this memoir. |